May 27, 2020

Planning Mombasa’s public transport system

Mombasa, Kenya’s oldest city, was founded in the 12th century due to its apt location as a spice trading centre. The city has since grown into a bustling metropolis with a population of 1.2 million. Mombasa is currently facing immense mobility challenges. Before the COVID-19 related economic slowdown, residents faced daily slowdowns on the roads headed into Mombasa Island, which forms the commercial core of the metropolitan area.

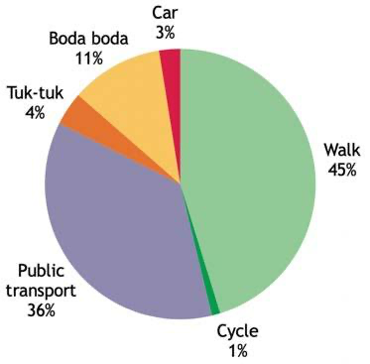

Due to shortcomings in the public transport system and a lack of safe facilities for walking and cycling, the city has been witnessing a shift to private cars and taxi services such as boda bodas and tuk-tuks. Public transport mainly consists of 14-seat matatus, which offer frequent service at certain times of the day but take a long time to fill up during off-peak hours. Vehicles are also often overloaded, and uncomfortable seating layouts make it difficult for passengers to board and alight. Most stops lack lighting and weather protection. The city also lacks adequate non-motorised transport infrastructure. Many roads have no provision for footpaths and cycle tracks and this has further encouraged the use of personal vehicles.

Traffic snarls have started occuring at low levels of motorisation—only 3 percent of the population uses personal vehicles, with the majority commuting by foot or using public transport. As activities resume amidst the pandemic, it is essential that future transport investments in the city accommodate the 45 percent of residents who walk and the 36 percent who use public transport. Adequate spaces for walking and cycling along with well-run public transport services are the need of the hour.

To help understand how the existing public transport system operates, ITDP in partnership with the Mombasa County Government began the process of developing a citywide public transport service plan. A service plan can help identify the most direct bus routes that serve the largest number of passengers in the most efficient way possible. A good service plan minimises the waiting time for passengers and the number of required transfers. It also identifies locations where dedicated infrastructure for public transport such as bus rapid transit (BRT) facilities can offer the greatest impact.

To assess travel patterns and identify which routes would benefit from improved public transport services, detailed surveys were conducted on the city’s matatu fleet, which numbers just above 4,000 vehicles. The surveys captured the frequency of routes, the number of people boarding and alighting at bus stops, public vehicle speeds, and passenger transfers. In Mombasa, information on the existing public transport system was limited and most services lacked route numbers, formal itineraries, and defined stops. As a result, the survey process identified these services through primary data collection.

Based on the frequency-occupancy data, Nyali Bridge, Makupa Causeway, and the Ferry terminal saw the highest passenger volume with 8,000 public transport passengers crossing Nyali bridge toward Mombasa Island during the morning peak hour. These corridors are strategic as they serve the main entry points into the island from the north, west, and south of Mombasa.

The global positioning system (GPS) tracks generated through the boarding-alighting survey showed that bus speeds in Mombasa are as slow as 5-10 km/h, especially on the approach to the CBD along Mtwapa Rd, Links Rd, and Old Malindi Rd and across Nyali bridge. Transfer survey interviews with over 2,100 matatu passengers revealed that a large number of passengers transfer one or more times to complete their journeys. Out of all journeys, 55 percent of passengers transfer once, 5 percent transfer twice, and 1 percent transfer more than two times. There is a clear opportunity to improve public transport service through better route planning and dedicated corridors for buses.

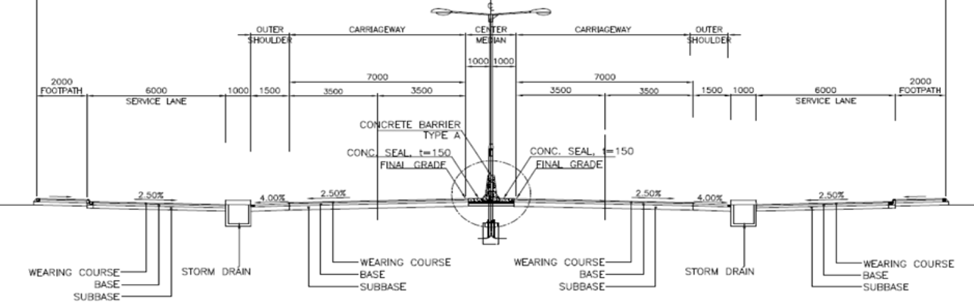

To reduce the congestion being experienced on major corridors, the Kenya National Highways Authority (KeNHA) has started upgrading the main arterial streets in the city. The Mombasa-Miritini road is being upgraded to a six-lane corridor, and the Mombasa-Malindi road is to be widened to eight lanes, with flyovers planned at major junctions. Both projects are being financed by the African Development Bank (AfDB). The cross sections include basic footpaths but no facilities for cycling or public transport.

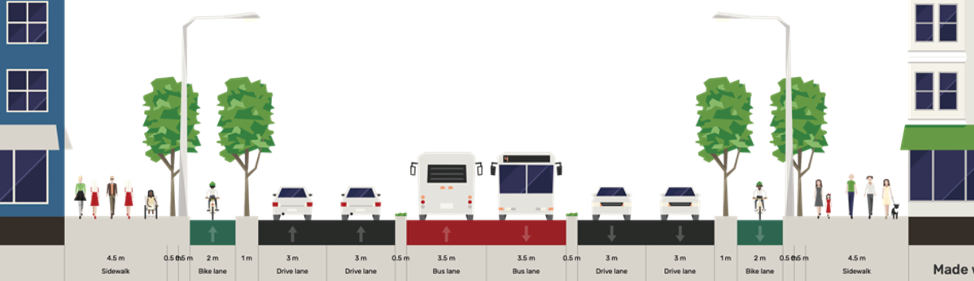

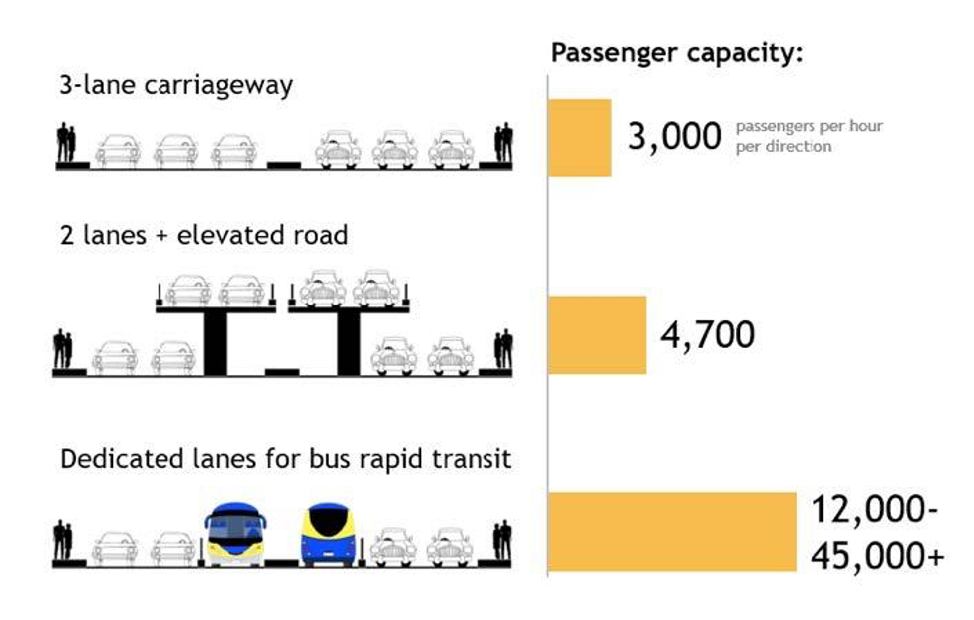

Cities around the world have found that road expansion without provision for public transport only attracts more traffic. The only viable long-term solution for ensuring improved mobility is to build high-quality facilities for public transport and non-motorised transport (NMT). Public transport can carry large numbers of passengers without an exponential increase in road space requirements. To make public transport service more competitive, major corridors in Mombasa could benefit from a dedicated road space for public transport in the form of BRT.

The Mombasa service plan identified a potential BRT network based on public transport passenger volumes, speeds for public transport passengers, ability to connect main trip generation areas, the presence of sufficient right-of-way (ROW) for median-aligned lanes and stations. The 15 km first-phase network links Posta, Mwembe Tayari and the ferry terminal with the northern catchment areas of Bamburi, Mtwapa, Kisauni and Mshomoroni. The BRT system would have 232 buses and 16 routes serving 245,000 passengers per day.

Implementing a BRT system on this network—including the Mombasa-Malindi road slated for widening under the AfDB-financed project—would yield significant benefits for city residents. Passengers would see their one-way commute travel times fall by 41 percent. In addition, the system has the potential to improve traffic flow by shifting trips from the numerous 14-seater matatus to larger vehicles in a dedicated lane. An effective industry transition process can help facilitate the modernisation of Mombasa’s matatu sector, which could then operate high-quality scheduled services.

Mombasa could benefit greatly from increased public transport investment, and the planned expansion of the Mombasa-Malindi road presents a timely opportunity to initiate this process. As the population in the city continues to increase, and with it, the number of personal vehicles, it is imperative that the growing levels of congestion are curtailed by incorporating mass rapid transit and NMT infrastructure in current and future road construction projects.

In an era of unprecedented infrastructure expansion in developing countries, development banks and global infrastructure funders have a crucial role to play in mitigating economic, social, and environmental trade-offs. Infrastructure projects should consider social and environmental impacts along with long-term economic benefits that can only occur if equity, diversity, and resilience are considered.